Welcome guest, is this your first visit? Create Account now to join.

Welcome to the NZ Hunting and Shooting Forums.

Search Forums

User Tag List

+ Reply to Thread

Results 61 to 75 of 81

Thread: 1000m rifle.... What?

-

02-09-2014, 07:10 PM #61VIVA LA HOWA

-

-

02-09-2014, 07:11 PM #62Banned

- Join Date

- Jul 2012

- Location

- Dannevirke, southern Ruahines

- Posts

- 5,072

-

02-09-2014, 07:17 PM #63

VIVA LA HOWA

VIVA LA HOWA

-

02-09-2014, 07:20 PM #64Banned

- Join Date

- Jul 2012

- Location

- Dannevirke, southern Ruahines

- Posts

- 5,072

-

02-09-2014, 07:42 PM #65

A case with to little taper is harder to eject than a tapered case especially when the brass gets old/fired a few times.

You just can't run them to their full potential because when you do they just won't eject especially if you have little or no primary extraction.

Most military cases have plenty of taper because that makes them more reliable in the field which is a very desirable trait if you are hunting something that can hurt you.

Fire forming is as easy as if you know what you are doing & only has to be done once for each case, just like neck turning, it just isn't as much of a PIA as most people make out.

A true AI chamber will accept a factory chambering happily if head spaced correctly.

Brass for an improved chamber needs to be fire formed carefully otherwise issues can arise which can lead to head separations, which combined with incorrect headspace & hot loads can result in a face full of nasty bits, particularly important to consider with improved chambering's without barrel designations & brass not formed in that particular chamber.Contact me for reloading components, brass, projectiles, powder, primers, etc

http://terminatorproducts.co.nz/

http://www.youtube.com/user/Terminat...?feature=guide

-

02-09-2014, 08:22 PM #66

@BRADS i was thinking of AI'ing my 270 but there is nothing to improve

-

02-09-2014, 08:24 PM #67Banned

- Join Date

- Jul 2012

- Location

- Dannevirke, southern Ruahines

- Posts

- 5,072

-

02-09-2014, 08:26 PM #68

-

02-09-2014, 08:27 PM #69

-

02-09-2014, 08:28 PM #70

-

02-09-2014, 08:29 PM #71

-

02-09-2014, 08:37 PM #72

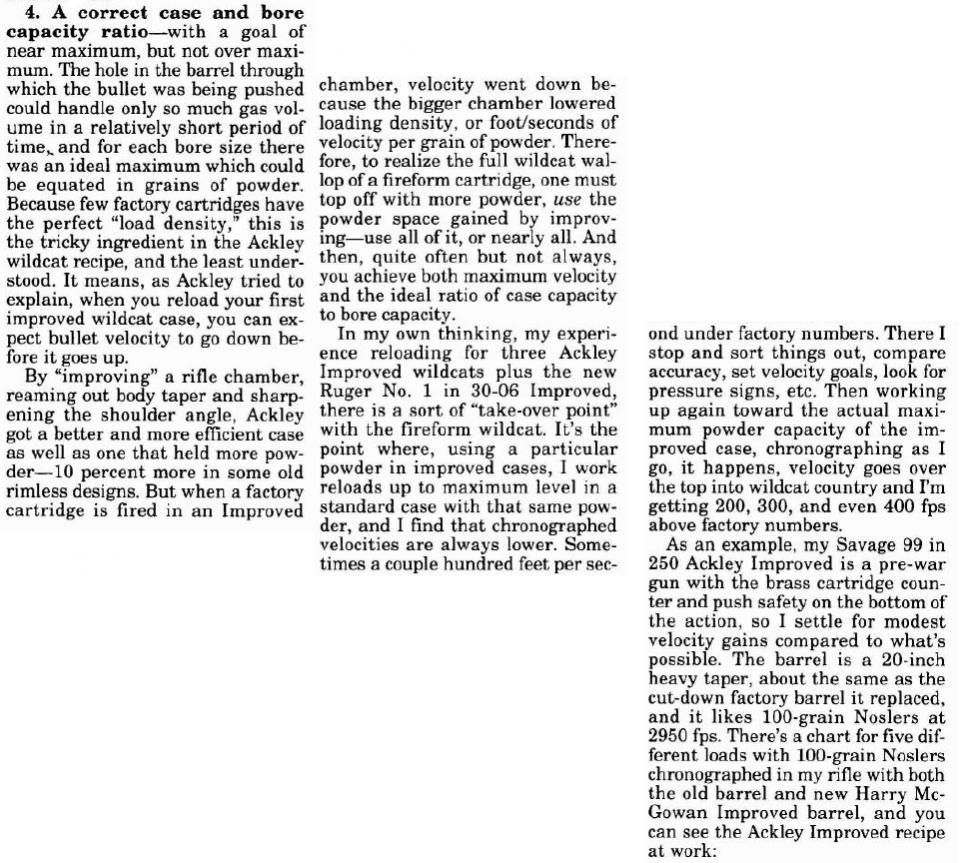

Love my .223AI, so much so that I'm in the process of having a slightly larger AI built.

They are easy to load for and make a lot of sense to me.

As long as the smith sets up the chamber for a very slight crush fit on the shoulder of the parent case, then any problems of excess head space shouldn't be an issue.

Brass stretch and subsequent trimming is almost non existent, and 100-150fps depending on parent case is usually the norm.

Maximum parent case loads are usually a good starting load for AI chamberings and fire forming loads are normally very accurate.

What's not to like?

-

03-09-2014, 04:39 PM #73Member

- Join Date

- May 2014

- Location

- New Zealand

- Posts

- 84

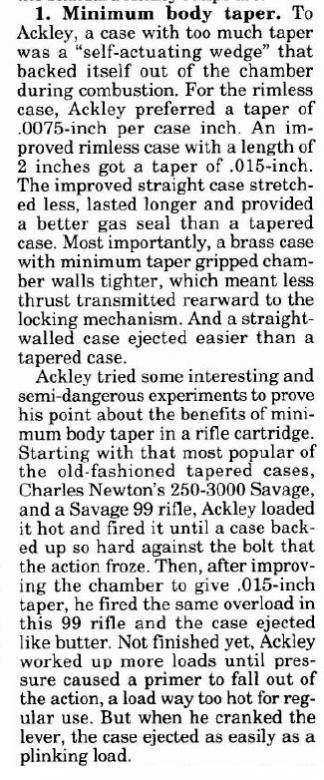

The Savage Model 99 is a rear locking action, hence the spring back with a hot load. So-called improved cases were initially developed in the U.S.A. in order to get extra velocity, through greater pressure, in relatively weak lever-action rifles, such as the notoriously weak Stevens 44 and 44-1/2 single-shot rifles using varmint cartridges; and various repeating types.

The U.S.A. and Britain engaged in a joint project after WWI to develop a lighter-recoiling cartridge which could be used in self-loading rifles, selective-fire rifles and machine guns. The British wanted a rimless cartridge that would feed and extract as reliably or better than the .303. The Yanks wanted to avoid the feeding and extraction issues that plagued the .30-06 more than any other modern rifle cartridge used in that conflict.

It wasn't just the Chauchat machine gun that failed with the .30-06. The machinegun that became the Vickers-Berthier and equipped the Indian army in WWII had problems with the .30-06 during the trials that culminated in adoption of the BAR. Increased taper and lower pressure were crucial parts of the equation. The long range target shooters in the U.S. Army sabotaged the process and the excuse given by MacArthur c. 1932? of existing ammo stocks was false, as those ammo stocks were all used up within the next several years, during a depression with cutbacks in training budgets!

The French adopted the 7.5x54MAS, an obviously tapered cartridge so close to the 6.5x55SE that Hornady used reformed 6.5x55 cases to develop their load data for it. When the yanks started work in 1941 to develop a new .30 calibre cartridge, they commenced their research with a thorough scientific examination of the aforementioned French cartridge. Subsequent adaption of the .300 Savage case probably resulted from a combination of cost saving imperatives (retention of existing rim size) and a desire to equal .30-06 ballistics (the 7.5x54 uses a 140gr projectile if I recall correctly).A good shot at close range beats a 'hit" at a longer range.

-

04-09-2014, 12:32 AM #74Member

- Join Date

- May 2012

- Location

- Wellington

- Posts

- 444

-

04-09-2014, 12:35 AM #75

Similar Threads

-

Ruger American RifleŽ Compact Bolt-Action Rifle Model 6914

By Eyesplice in forum ShootingReplies: 17Last Post: 10-03-2015, 11:06 PM -

New rifle for goat control/sons first rifle

By Tristan in forum Firearms, Optics and AccessoriesReplies: 43Last Post: 08-08-2014, 08:50 AM -

Bruce Rifle Club Service Rifle Competition 2013

By fernleaf in forum ShootingReplies: 11Last Post: 28-10-2013, 07:38 PM -

Large rifle/small rifle case holder

By R93 in forum Reloading and BallisticsReplies: 5Last Post: 16-04-2013, 09:25 AM

Tags for this Thread

Welcome to NZ Hunting and Shooting Forums! We see you're new here, or arn't logged in. Create an account, and Login for full access including our FREE BUY and SELL section Register NOW!!

92Likes

92Likes LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks